f/64 - Revolution in Focus

Smoky Symbolism yields to Photographic Detail

In 1932 fine-art photographs looked alot like paintings; at least like romantic, highly stylized and symbolic paintings. The pictorialist style of photographs were 'created' (as opposed to faithfully recorded) to imbue atmosphere and allegory. As result, pictorialist photographers printed to rough texture paper, and with means to emphasize soft focus. Creating outline for the subject with a chiaroscuro of definition between negative and positive space, was prized over acuity of object.

Pictorialist style held economic and political rationale - pictures appearing like paintings could be sold to gallery owners while mere photographic recordings could not.

Miss N (Evelyn Nesbit) - by Gertrude Kasebier

Pictorialist portrait photographer Kasebier was one of the most celebrated and well paid artists of her time. Note the allegorical grasp of the pitcher and forward leaning voluptuous pose, typical to pictorialist style.

Image created in 1898 and published within Camera Work 1 in 1903.

One of the prominent gallery owners was Alfred Stieglitz, whose 291 Gallery in New York would curiously show culturally resistant, 'postmodern' art (like Francis Picabia, a Cubist - Dada artist) but not Edward Weston, an anti-pictorialist photographer.

So in 1932, over dinner, a group of photographers gave name to their political resistance to pictorialism: f/64. The name was simple. Derived from the technical act of optically rendering a highly detailed image. When a camera's lens held its smallest aperture (usually f/64 for large format cameras of the time), the greatest depth of field is applied to the subject. If camera motion did not intervene, the object was rendered in great detail.

f/64 was a manifesto, described in the technical apparatus of photographic image making.

Yet image content, not technical rendering, was also a primary message of f/64. As described by Beaumont Newhall in Photography: Essays & images.

"The members of Group f/64 believe that photography, as an art form, must develop along lines defined by the actualities and limitations of the photographic medium, and must always remain independent of ideological conventions of art and aesthetics that are reminiscent of a period and culture antedating the growth of the medium itself."

Eleven f/64 photographers were assembled at the 1932 dinner party, which was in honor of Edward Weston. Edward himself had shifted from earlier pictorial images to high detailed images of peppers, artichokes, sea shells and other objects, made heroic through the medium-specific advantages of close-up photographs. For example, see Weston's famous Pepper 1930. By contrast to Weston, pictorialist artist WIlliam Mortensen was using the camera to emulate painterly mediums - so as to appear more like a graphite drawing on rice paper, as in the work below.

William Mortensen's Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam is a pictorialist interpretation of a scene from the film by Ferdinand Pinney Earle, depicting the popular book of moral allegory by Omar Khayyam. Mortensen was a successful Hollywood photographer who used stage lighting for dramatic enactments of scenes which predated the birth of photography in 1839.

Before and After Pictorialism

Above are side-by-side images showing Edward Weston's transformation from pictorialism to f/64 realism.

- Epilogue 1919

- Cabbage 1931

- Self Portrait 1915

- Shell 1927

Obvious differences are use of studio vs natural lighting, in particular high-key, theatrical lighting. Weston ran a portrait studio just miles from Hollywood, where oriental motives made box office sales (like Shanghai with Marlene Dietrich - 1932). The oriental fan in Epilogue, is such an object carried over from popular culture, post World War I. Weston's Self Portrait, continues with direct studio lighting, applying narrow focus and textured paper is used to soften the overall effect and apply the pictorialism which brought paying customers to his studio. Cabbage and Shells are deep departures from the theatrical subjects of a decade earlier, yet the sensuality and drama remain apparent even in the simple extracted view or organic objects. Sensuality was to continue in Westons' work throughout his life.

Ansel Adams, another of the f/64 photographers, and perhaps today considered the most important photographer of the 20th century, declared Mortensen as "the Anti-Christ". Why such vehemence? Likely because of Mortensen's recognition on the West Coast as a fine art photographer and his pictorialist vernacular style.

Mortensen ran a school in Los Angeles and was a frequent contributor to the Los Angeles Times - he was well known publically as a photographer-artist, while Adams was not. Adams enjoyed a minor prominence from the Sierra Club and exhibited with the organization on images taken in the High Sierras, yet Mortensen was the better known, more popular image maker. Adams distaste for Mortensen was manifested in his theatrical images and emphasis on psychological motives, with pictorial impact from direct studio lighting, soft focus and textured papers.

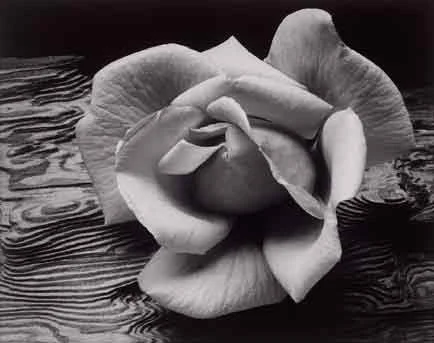

Adams, like Weston were de-emphasizing religious, mythical and allegorical themes - preferring subjects from nature for which no messaging was implied other than the sublime beauty to be found in natural objects.

Ansel Adams - Rose and Driftwood 1932, as an extracted image from nature, was a subject highly prized by f/64 photographers due to the detail rendered by entirely photographic means and its subject which was without allegory.

As Edward Weston phrased it, "The camera should be used for a recording of life, for rendering the very substance and quintessence of the thing itself, whether it be polished steel or palpitating flesh."

It becomes clear that the camera itself was being elevated in stature as an instrument of fine art by f/64 photographers, whereas Pictorialists were doing their best to sublimate the use of the camera preferring instead images which could be mistaken as watercolors or pencil drawings.

Kodak - You Push the Button and we Do the Rest

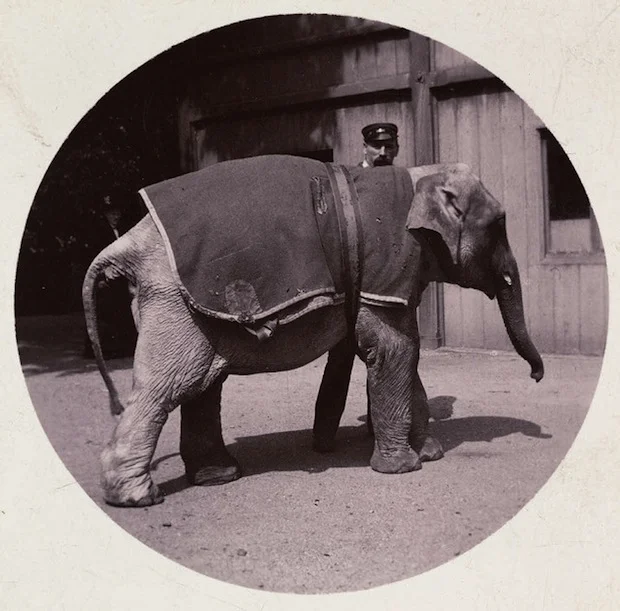

Kodak's first camera was put in the hands of consumers in 1888 and created an explosion of photography due to the ease and speed over previous individual dry plate or wet plate methods. Now a roll of film was available - in fact 100 images could be recorded before processing. Consumers needed no kit, chemicals or methods of presentation - instead the camera and images were returned ready made. As returned to the consumer, fresh film was loaded in the camera, and the circular images (above 'Elephant' - Photographer Unknown) were fitted to square cards. A convenient package to disseminate to friends and family.

The first Kodak camera created a problem for pictorialists and f/64 photographers alike.

Popularization of image making required a differentiation for fine artists. Kodak's first camera in 1988 was not unlike the introduction of the smartphone camera in the early 21st century. It can be estimated the shift from dry plate on glass to roll film increased photographic image making by more than 1000 times. And the importance of a Smartphone with camera can be understood in the following statement: more photographs have been taken in the time to read this blog post than all the photographs made in the previous two centuries.

Thus in 1888 began an explosion of image making which was unprecedented as George Eastman removed the inhibitors of photography. The general public began to identify socially and culturally with cameras as a means to document all aspects of life, possibly the most important social medium second only to motion pictures.

So what impact did Kodak have on pictorialist? It meant pictorialist needed to differentiate from the common act of photography by mimicking the high art of painting. And impact did Kodak have on f/64 photographers? It meant elevating the optical quality of the image through higher levels of detail and use of focal point unattainable to the Kodak's first camera.

Despite the advent of 'Kodakery' and "Kodaking", f/64 photographers aspired to use of the camera to its greatest technical achievement, and for this downplay of optical capability by pictorialists was an offense in elevating the importance of the science and art of photography.

Transition #1 - the "anti-Christ" of Pictorialism (1932)

The first rebellion in the visual art described as photography, came in the reaction of the f/64 group to pictorialism.

Although pictorial painting had given way to several modern art movements by 1932 ( for example: Impressionism and Dadaism, in painting, and International Style in architecture), popular views on art were based on pre-Raphelite painters like Rosetti's 1887 - Beata Beatrix, which can readily be compared to compositional elements in Kasebier's 1898 - Miss N.

Kodakery, and the rise of amateur photographers, amplified the f/64 refusal to mask or disguise the science within photographic art, as the advancement and limitations of a camera, its optical lens and photographic emulsions, was becoming obvious - one snapshot at a time.

In the 2017 Los Angeles The Autry at Griffith Park show - Revolutionary Vision: Group f/64 and Richard Misrach Photographs - Amy Scott, Chief Curator of Visual Arts, compares Misrach in similar transition and refusal of present style. In the 1970's and into the early 1980's - fine art photography were decidedly black and white. Misrach, Stephen Shore, Elliot Porter and photographer William Eggleston begin to elevate color as the new state of photography.

So the themes of Transition #1 (photo vernacular detail, lack of Pre-Raphelite allegory, and the American West) beget Transition #2 - the Elevation of Color - as example in the California vision of Richard Misrach's Submerged Lamppost, Salton Sea, 1985 (above).